At the beginning of this month at the Lateran University, in Rome, we began the course on iconography, opening us up into a world that many Christians rarely think about. Iconography is the study of icons or symbolic representations.

By Jonah M. Makau *

Iconography should not be confused with iconology, which goes beyond the visual elements and delves into the deeper cultural, historical, and contextual significance of those symbols and images. In other words, while iconography refers to the study and interpretation of symbols and images used in art, focusing on the visual representation and meaning they convey, iconology focuses on their social cultural part of the same. As you may have noted, the two compound words begin with the word “icon”, which means image. As such, iconography and iconology deal with images, but as we have seen, looked at from different angles.

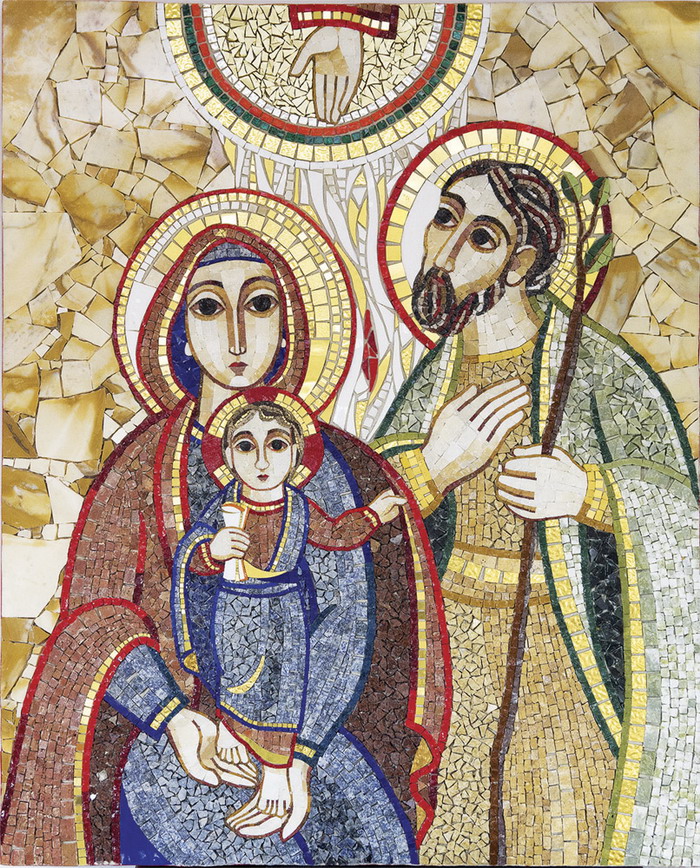

Images have a long history in the churches. The recognition of Christianity by the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great, was the beginning of the “adornment” of churches with icons, which until then were limited to private use only. The icons were used to depict themes from Christ’s life, the life of His mother Mary and scenes from the Bible or from the lives of Saints. That way, even those who could not read the bible, (which the lay people were also not allowed to read), could understand the mystery of God’s self-revelation and his work of salvation. The figures and the scenes portrayed in the icons or the wall paintings, were based on oral information passed from mouth to mouth among the faithful. The first icon is attributed to Luke the Evangelist and depicts Virgin Mary. In the 8th century and the first half of the 9th century in the Byzantine Empire, icons became a subject of theological and political conflict which caused unrest in the empire and beyond, separating the Christian faithful into icon lovers (Iconodules) and to those fought icons (iconoclasts).

Today, icons are an integral part of the expression of our faith. In fact, just as it has been over the centuries, icons are a form of prayer and a “means” of praying. They assist in worship. That is why they are referred to as a ‘window to heaven’ since they help us to focus on the divine things. While they still contain material aspects, like paint and colour, through them, we are taught not to reject our physical life but instead to transform it, as was done by the holy people represented by the icons. It is important to note that the icons themselves are only venerated, not worshipped. We only worship God in the Holy Trinity.

Unlike one time when icons were a means of learning the mysteries of God for illiterate people, today icons are almost sacramental. This means that they make historical events present, through representation of the divine realities in visible form. They have since transcended the didactic function they offered one time. Their whole point is to lead us beyond what can be apprehended at the merely material level, to awaken new senses in us, and to teach us a new kind of seeing, which perceives the Invisible in the visible. The icons are also eschatological in that they are images of hope. They give us the assurance of the world to come, and of the final coming of Christ. Certainly, the icons are Christological in nature. The icon of Christ is the centre of sacred iconography and the centre of the icon of Christ is the Paschal Mystery.

Unfortunately, today we are experiencing, not just a crisis of sacred art, but a crisis of art in general. Due to the decrease in faith or what many people see as spiritual blindness, the church (and the world) is facing a crisis of unprecedented proportions. Secularism, individualism, and materialism have killed the sense of sacred in our hearts, to an extent that artist no longer present the invisible through their talents as they used to do. With the monetization of their artistic gifts, they have failed in their responsibility of helping the world to see the invisible through different themes presented in line, colours and shades. The same thing has happened in music. While one time the artists saw themselves as special tools of the Invisible to speak to his people, today the creativity of the artist and the amount he can make from a given piece of work is what counts. Strangely, even singing that is supposed to be “praying twice” is no longer so.

Simultaneously, we, the consumers of art have lost the sense of true beauty, which speaks through the artistic work of artists. A good example of this is that we have lost the senses of quality and modesty, and moved to external attractive beauty that no longer points beyond itself. For many of us, the more abstract an image is, the more spiritual it is. We no longer differentiate between abstractness and spiritual-ness of art. That is why we are ready to put any image in the church, as long as it has a character who vaguely resembles Christ, the Blessed Virgin Mary, the saints, and so on. We have forgotten that our faith is as healthy to the extent of the image of God and the saints that we have in our minds and hearts.

As pope Benedict XVI noted, the truth does not only set us free – it also enables us to see. Without it, we will not behold the beauty of the cosmos as made manifest in the music of the spheres. Without faith and good relationship with God, whenever we look at a piece of work of art, we will see nothing but mere matter. And if there’s nothing but mere matter, nothing really matters, including beauty. The truth is that the beautiful is inseparable from the good and the true. What is needed is the gift of a new kind of seeing, which does not depend only on the bodily eyes. It important to ask the Lord in this time of Lent to give us a faith that sees, because that is the only way to discover that Christ is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation (Col 1:15).

* Fr. Jonah M. Makau, IMC, is taking a course of postulation in the Lateran Pontifical University in Rome.